|

Constance Markievicz (1868 - 1927)

Irish Revolutionary,

Suffragette, Citizen Army Soldier, Easter Rising Participant,

First Female elected to the Westminster

Parliament, and Labor Minister in the First Dail

Eireann

Constance

Markievicz was prominent amongst a number of

brave women born into the British aristocracy who

through their exposure to the abject poverty of

the native Irish under British colonial rule

and the systemic destruction of their cultural

identity became leaders in Ireland's struggle

for independence and for the preservation of its

unique cultural identity. Constance's commitment

to Ireland was total and uncompromising, a

commitment that led to vilification by her

former peers, a commuted death sentence, and

numerous terms of imprisonments. Her place in

modern Irish history is secure and beyond

reproach, and her exploits are immortalized

alongside those of Ireland's greatest heroes.

Early

Carefree Years Early

Carefree Years

Constance

Gore-Booth was born on February 4, 1868, at

Buckingham Gate in London, the eldest of three

daughters and two sons born to Henry Gore-Booth

and Georgina Mary Gore-Booth, nee Hill. Shortly

after Constance's birth, the family relocated to

their Lissadell estate in Drumcliffe, Co.

Sligo. She and her four siblings---Josslyn,

Eva, Mabel, and Mordaunt---were the third

generation of Gore-Booths to live in Lissadell

House, which was built for her paternal

grandfather, Sir Robert Gore-Booth, in the early

1830s.

Constance’s father, Henry Gore-Booth, was a

landowner, Arctic explorer, and author of

articles on Arctic exploration and other

Arctic-related topics. He succeeded to the

Gore-Booth Baronetcy of Artarman in Co. Sligo

after the death of his father, Sir Robert

Gore-Booth, in 1876. The Baronetcy, created in

1760, comprised a title, a 32,200-acre estate,

and a residence, Lissadell House. Sir Henry did

not involve himself in politics, preferring

instead to focus on the management and

development of the estate. In addition to his

estate-related duties, he served as president of

the Sligo Agricultural Society and chairman of

the Sligo, Leitrim, and Northern Counties

Railway. He also held a number of appointed

ceremonial and administrative-type positions

including High Sheriff of Sligo, Deputy

Lieutenant, and Justice of the Peace. By all

accounts he was a good landlord who cared for

his workers and tenants, and took care that they

were fed and clothed during the famine of

1879/80. That was in contrast to his father, Sir

Robert, who, during the Great Hunger years of

the 1840s, cleared his estate of workers and

tenant farmers by packing them into leaky,

overcrowded coffin ships and shipping them off

to Canada and America.

Constance's mother, Georgina, the daughter of

Colonel Charles J. Hill, a British Army officer,

and Lady Frances Charlotte Arabella

Lumley, established a school at Lissadell to

train women in crochet, embroidery, and

darn-thread work. With their new acquired

skills, the women were able to earn a wage to

supplement their meager household income. That

undertaking by their mother, and the way their

father cared for his workers and tenants during

the

famine

of 1879/80, had a positive influence on

Constance and her sister Eva that would factor

into their evolving life choices.

Constance,

as well as her siblings, had the most idyllic

childhood one could imagine, growing up and

coming of age on a vast estate on the shores of

Sligo Bay, within sight of Benbulbin. She wanted

for nothing. Horseback riding, sailing, parties,

and travel filled her carefree life. The meager

existence of the estate's servants and workers

was a fact of life that did not unduly concern

her. Despite that, she mingled with them and

treated them with respect. The fear and

disruptions caused by the famine of 1879/80 was

an early learning moment for Constance, a

reminder that life could be cruel and merciless

for the working class, and that their plight

could impact her life also. That experience in

itself did not change her charmed lifestyle. It

would be many years later before Constance cast

aside the trimmings of nobility and donned the

cloak of social reform and revolution.

Constance

and her female siblings, Eva and Mabel, were

educated at home by governesses. As was

customary in the prevailing

patriarchal-dominated society, her male siblings

were sent off to exclusive boarding schools and

universities for their education. Constance was

intelligent and somewhat rebellious, more

interested in exploring the countryside on her

pony than conforming to the niceties of high

society. In addition to her mastery of the

literacy and numeracy skills, Constance was

fluent in French, German, and Italian. She also

demonstrated a talent for painting. As part of

her education, she did the customary Grand Tour

of Europe. In 1887, at the age of nineteen, she

was presented to Queen Victoria, as was the

custom for young ladies of her station in life.

Ever since

the famine of 1879/80 the winds of change were

blowing across the Irish landscape and fanning

the ever-present discontent between landlords

and tenant farmers, particularly in the west of

Ireland, the area most impacted by the famine.

Constance was still too young to understand the

implications of what was happening next door in

Co. Mayo where

Michael Davitt was organizing tenant farmers

to resist unreasonable rent increases and

arbitrary evictions by landlords. Despite the

ongoing demonstrations, evictions, boycotts,

killings, and heightened political activity, the

Gore-Booths ignored all of it as it did not

directly impact them. As politics and social

issues were taboo within the confines of

Lissadell, Constance was unaware of the rising

tide of Nationalism and anti-imperialism

sweeping across Ireland.

Early Activism and Marriage

Shortly

after completing a European tour in 1892 with

their mother, Constance and Eva set out to forge

their own life's journey and assert their

independence, notwithstanding the fact that they

were still reliant on their parents for the

finances to support their nascent independence.

Constance, who was a talented amateur painter,

enrolled in the

Slade School of Art in London to improve her

painting skills and gain professional status.

Eva went to live in Manchester with English

suffragist and pacifist Esther

Roper

whom she had met on the

European tour. The two women would

spend the rest of their lives together, working

on social issues ranging from workers’ rights to

capital punishment.

During

subsequent visits to Lissadell, both Constance

and Eva became involved in women's suffrage, to

the consternation of their parents. They founded

the Sligo Women's Suffrage Association in 1896

and held information and recruitment meetings

explaining to women what the issues were and why

they should join the organization. At one such

meeting in Drumcliffe, Constance made a rousing

speech touting, amongst other accomplishments,

the increasing number of women attending

meetings and signing petitions in support of

women's suffrage.

It was

also during these visits to Lissadell that

Constance and Eva met and became friends with W.

B. Yeats who frequently visited the Gore-Booths

in Lissadell during visits to his uncle in

nearby Thornhill.

In 1898,

in furtherance of her art studies, Constance

enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian in

Paris where she met her future husband, Casimir

Markievicz. Casimir, an artist and scion of

a wealthy Polish family, was married with two

children when they first met. He was separated

from his wife at that time. In September of

1900, after the death of his wife, Constance and

Casimir were married in London. In 1901, the

Markieviczes visited Lissadell where Constance

gave birth to their daughter, Maeve. After

spending some time in Lissadell, they

visited Paris and the Markieviczes' estate in

the Ukraine. In 1903 they returned to Dublin

with Casimir's surviving son and took up

residence in Frankfort Ave., Rathgar.

Constance's reputation as a talented landscape

artist brought her in contact with other

artists, writers, and actors, many of whom were

involved in the Gaelic League and other

Nationalist-leaning organizations. At that

time, she was still apolitical, more interested

in the suffrage movement and the arts than in

the affairs of state. Her interest in the arts

found expression in the presence of such

notables as

Lady Gregory, cofounder of the Abbey

Theatre; George

'AE' Russell, writer and Irish Nationalist;

Thomas MacDonagh, poet, playwright, and

Irish revolutionary; and W.

B. Yeats, poet and dramatist whom she knew

from her days in Lissadell.

The

Markieviczes became close friends with AE who,

after first meeting Constance, opined that she

embodied the spirit of a rebel. Always willing

to do favors for friends, AE arranged to have

the Markieviczes' paintings displayed alongside

his own at various exhibitions. He also gave

Constance a part in his play Deirdre, performed

at the Abbey in 1907.

Over the

years Constance appeared in a number of other

plays in the Abbey. In 1908, she was cast as

Maeve in Edward Martyn's Maeve, and also as

Daphne Tisdall in Casimir's Seymour's

Redemption. In 1910 she was cast as Norah in

Casimir's The Memory of the Dead. Through 1912

she was cast in a number of other plays staged

in Dublin and elsewhere throughout the country.

In 1905,

in collaboration with some of her newfound

friends and acquaintances, Constance cofounded

the United Artists Club to bring together

members of the arts and literary communities to

discuss and collaborate on issues of common

interest. It was at the club's meetings that

Constance met many of Ireland's luminaries

including Michael Davitt, John O'Leary, Douglas

Hyde, Arthur Griffith, and

Maud Gonne.

Transition to Nationalism

1908 was a

pivotal year for Constance. She journeyed to

Manchester to support her sister Eva and her

partner Esther Roper and other suffrage

activists in their campaign to defeat Winston

Churchill in the Manchester Northwest

parliamentary by-election for his refusal to

oppose legislation that prohibited women from

working after 8:00 pm. Though they succeeded in

denying him the seat, Churchill won a

by-election in another nearby constituency a few

months later.

Also in

1908, at the invitation of

Helena Moloney, Constance joined Maud

Gonne's

Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of

Ireland) whose stance was political, social, and

feminist. Its aims were to de-anglicize Ireland,

foster the creation of a sovereign Irish nation,

and promote Irish manufacturing. After joining

the organization, Constance helped Helena

Moloney and

Sydney Gifford launch Bean na hEireann

(Women of Ireland), a monthly news journal

advertised as the first Irish women's paper.

Constance designed its masthead and contributed

articles on gardening and on a number of other

issues impacting women until it ceased

publication in 1911.

Encouraged

by Bulmer Hobson, a member of the Irish

Republican Brotherhood, Constance joined Arthur

Griffith's

Sinn Fein (We Ourselves), an umbrella

organization whose original aim was to achieve

Irish independence under a dual monarchy similar

to the Austria-Hungary model. As the

organization evolved, its aims also evolved away

from Griffith's dual monarchy model and pacifist

beliefs. Soon after Constance was elected to its

executive she was caught up in the maneuvering

between factions as to whether the organization

should join a breakaway group of the

Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) in

contesting seats in the 1910 general election.

After the proposal to join the breakaway failed,

and Sinn Fein lost the 1908 North Leitrim

by-election, the party lost support. Sinn Fein

split into a Home Rule faction and a militant

faction, which was supported by Constance.

Early in

1909 Constance rented a cottage at Sandyford in

the foothills of the Dublin mountains where she

and Casimir could get away from the city and

find quite spots to paint. The last occupant of

the cottage was Padraic Colunm who left books,

pamphlets, and newspapers behind. Leafing

through the trove, Constance came across

Robert Emmet's speech from the dock.

Intrigued by Emmet’s courage and sacrifice, she

embarked on a quest to thenceforth educate

herself on Ireland’s quest for national

sovereignty. To that end she read about Eoghan

Rua O’Neill,

Wolfe

Tone, Thomas Davis, and other heroes of

Ireland's past. From what she learned it was

evident to her that many of Ireland's sons and

daughters had not surrendered or acquiesced to

the conquest of Ireland. She also realized that

many of her new friends were of the same

mind-set as Tone and Emmet. From then on,

Constance's transformation from a progeny of

imperial privilege to a fervent Irish

revolutionary was irreversible.

Having

fully embraced Irish Nationalism, Constance

revised her approach to women's suffrage to

include national sovereignty as an issue of

equal importance for Irish women as both were

inherent basic rights denied them because of

their gender and race. Going forward, her

speeches to suffrage gatherings were laced with

Nationalist rhetoric implying that the forces

denying women their rights were the same forces

denying their homeland its right to national

sovereignty, therefore they should fight for

both. She also encouraged women to unionize and

not to depend on men for

leadership. Nonetheless, she encouraged women to

support

James Larkin, the founder of the Irish

Transport and General Workers Union, and his

successor James Connolly, both of whom treated

women as equals.

Militancy and Revolution

Perhaps

the more enduring aspect of Constance's legacy

was

Na Fianna Eireann

(The Fianna of Ireland),

an Irish Nationalist youth organization she and

Bulmer Hobson founded in August of 1909. When

she initially discussed the idea with Sinn Fein,

they rejected it out of hand, stating that they

had no intention of creating a military arm. Not

deterred by their rejection, Constance went

ahead and founded the Fianna, perhaps the most

consequential decision of her life. The Fianna's

accomplishments were many and history making and

included the launch of the

Irish Volunteers, the Howth and Kilcoole

gunrunning operations, the 1916 Easter Rising,

the War of Independence, and the Treaty War

(Civil War). Padraic Pearse stated before his

execution "that without the Fianna there

would be no Volunteers in 1913 and no Rising in

1916".

In the

latter months of 1909, Constance leased Belcamp

House and the surrounding acreage located on the

north side of Dublin for use as the Fianna

headquarters and as a self-supporting farm and

market gardening enterprise. It was also

intended to be a learning center where the

Fianna boys would learn how to grow and harvest

fruits and vegetables. The boys who came from

the Dublin slums had no interest in farming,

preferring instead to spend their time camping,

drilling, and in shooting practice. In 1911,

after the enterprise failed to gain traction,

Constance was forced to vacate Belcamp House.

In 1911

during a visit to Belfast to lecture to the

Fianna, Constance met Ina and

Nora Connolly who had helped organize the

Betsy Gray sluagh (army), the only Fianna sluagh

for girls in Ireland. After the lecture, the

girls brought Constance to their home where she

met their father,

James Connolly. She was captivated by

Connolly's take on Nationalism and how he viewed

the fight for Irish freedom as inseparable from

labor rights and women's rights, the core

elements of a just society. Unlike many of his

fellow Nationalists and labor leaders, Connolly

was a feminist who believed that women should be

equally represented in all aspects of life and,

when the time came, as soldiers in Ireland's

fight for freedom.

After

embracing Connolly's definition of a just

society, Constance included the exploitation of

labor in her ever-expanding repertoire of

deserving causes. Going forward, her speeches

argued that women's rights, labor rights, and

cultural and political rights were unachievable

under British colonial rule, therefore Irish

independence was the porthole to freedom and to

a just and equitable society.

In 1911

Constance and

Helena Moloney were arrested for taking part

in a demonstration against the visit of King

George V to Ireland. After being manhandled by

the police Constance was released the following

day without charge. Around that same time, she

joined in the campaign with Connolly, Larkin,

and Maud Gonne to extend the 1906 Provision of

School Meals Act to Ireland.

In 1912,

Constance and Casimir rented the Surrey House on

Leinster Road in Rathmines. During the four

years that she lived there, Surrey House was an

open house for political activists, including

Liam

Mellows, Bulmer Hobson, James Connolly,

James Larkin, and the Fianna boys, as well as

for members of the arts community. It housed a

printing press where posters, pamphlets, and

other protest-related materials were designed

and printed. It also was one of the hiding

places for guns from the 1914 Howth gunrunning

operation.

During the

Dublin Lockout in 1913, Constance, Delia Larkin,

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington,

Seán O’Casey, and other volunteers set up

kitchens in Liberty Hall to feed the locked-out

workers and their families. Every day for the

duration of the Lockout, Constance cycled from

her home in Rathmines to Liberty Hall to oversee

the collection of food and help in the kitchens.

Although the Lockout ended in failure for the

trade unions and many of the business owners, it

nonetheless established the role of trade unions

as a force to be reckoned with in labor disputes

and workers’ rights in Ireland.

One legacy

of the Lockout was the founding of the

Irish Citizen Army (ICA) whose original

purpose was to protect union demonstrators from

the police who were baton charging, beating and

killing unarmed demonstrators and passersby at

the behest of the business owners. The ICA was

founded on November 23, 1913, by Larkin,

Connolly, and other officers and members of the

Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union.

Constance was a member of its executive council

and a co-treasurer.

On

November 25, two days after the founding of the

ICA, the Irish Volunteers was founded at the

Rotunda in Dublin. Its purpose was to counter

the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) founded in 1912

to oppose Home Rule for Ireland and maintain the

union with Britain. In 1914, John Redmond

co-opted 75% of the Irish Volunteers to fight

for the British Empire in WWI. The Volunteers

who heeded Redmond’s call were renamed the

National Volunteers. Those who ignored his call

retained the original name, the Irish

Volunteers.

The

Easter Rising and Its Aftermath

During the

years 1914 and 1915, a series of consequential

events transpired within and outside of Ireland

that factored into the decision to launch

the Easter Rising of 1916. These events

included the passing and subsequent suspension

of the 1914 Home Rule Act for Ireland, the

Curragh mutiny by British Army officers, the

Larne and Howth gunrunning operations, the onset

of WWI, the co-opting of the Irish Volunteers,

the British Army's enlistment campaign, and the

all-important convergence of Irish cultural and

political Nationalism. As all of these events

unfolded, the ICA had morphed from a

workers-type security detail to a fully fledged

militia, ready to do battle for freedom and a

just society. As the downward spiral to

insurrection continued, Constance participated

in military training and preparedness alongside

her ICA compatriots. One of her closest

compatriots in that endeavor was

Margaret Skinnider

from Glasgow who, like Constance, was an

excellent markswoman, courageous and ready to

fight.

On Monday

April 24, 1916, at the onset of the Easter

Rising, Constance arrived at St. Stephen's

Green/College of Surgeons garrison where she

assumed her role as second-in-command to

Michael Mallin. During the ensuing week,

Constance was, as most accounts suggest,

responsible for neutralizing four British

combatants and possibly others lodged in the

Shelbourne Hotel from her sniper perch in the

College of Surgeons. She may also have killed or

wounded a policeman who tried to prevent entry

to the College of Surgeons during the retreat

from St. Stephen's Green.

On Sunday,

April 30, the garrison surrendered after

receiving a surrender order from

Padraic Pearse,

the Commander in Chief of the Irish

Volunteers. After surrendering their arms at the

College of Surgeons, the ICA Volunteers,

including Constance, were arrested. After a

trial before a British Field General Court

Martial, a secret trial without a defense or

jury, Constance was sentenced to death by firing

squad. To her dismay, the death sentence was

commuted to life in prison because of her

gender. The real reason for the commutation may

have to do with the specter of executing a woman

before a firing squad, a gruesome spectacle that

would tarnish the British oft-touted portrayal

of their presence in Ireland as that of a force

for good, a welcomed and benevolent ruler.

After

Constance's sentence was commuted to life in

prison, she was moved to Mountjoy jail in Dublin

before being transferred to Aylesbury prison in

Buckinghamshire in England where she would serve

her sentence.

In the

meantime, the sentiment in Ireland changed from

originally opposing to supporting the Rising due

to the arbitrary and barbaric executions of the

Rising leaders and the random and widespread

arrests and imprisonment of thousands of

noncombatants in its aftermath. That sentiment

manifested itself in the defeat of Irish

Parliamentary Party (IPP) candidates in a number

of subsequent by-elections. The IPP supported

Britain's handling of the Rising but warned

against the subsequent executions, a warning the

British ignored.

Simultaneously, Britain's efforts to convince

the United States to join in its war with

Germany were faltering due to the U.S.

Declaration of Neutrality, a policy supported

by the American public but not necessarily by

the Wilson administration. Ongoing efforts by

President Wilson to circumvent that policy were

vehemently opposed by noninterventionist and

pacifist groups. The most vocal and possibly

influential of these groups were the Irish who

opposed helping Britain and its Empire after its

brutal slaughter of Irish children and civilians

during the Rising and the barbaric execution of

prisoners of war afterwards.

In an

attempt to mitigate these setbacks, the British

government opted to grant a general amnesty to

all prisoners rounded up and imprisoned after

the Rising. Constance was amongst those released

on June 18, 1917. She was greeted back in

Ireland on June 21 by cheering throngs along the

train line from Dun Laoghaire to Dublin City.

Once

released, Constance resumed her work with the

labor movement, promoting the rights of Irish

women workers and raising funds for the James

Connolly Labor College. She also supported Sinn

Fein candidates running for seats in a number of

constituencies including the East Clare

by-election where de Valera won the seat. After

a number of such by-election losses the British

government tried to stop Sinn Fein from further

upsetting the applecart by arresting a number of

its leaders, including

Thomas Ashe who

later died on hunger strike.

In April

of 1918, after the death of John Redmond, the

British government extended the Military Service

Bill, aka conscription, to Ireland. The reaction

in Ireland was swift and substantial. The Irish

Parliamentary Party and its offshoot, the

All-for-Ireland League, joined forces with Sinn

Fein and Labor in opposing the provisions of the

Bill that applied to Ireland. The Catholic

hierarchy, who never opposed the British

presence or imperialist policies in Ireland,

threw its support behind the effort. As a

consequence, the British government balked and

did not proceed with its implementation.

Smarting

from their failure to implement conscription in

Ireland, the British blamed Sinn Fein. In

retaliation they arrested and interned, without

charge, 73 leading Sinn Fein members, including

all their elected representatives. Constance

was amongst those arrested in order to stop her

from demonstrating against conscription and

advocating for the end to British rule in

Ireland and the establishment of an Irish

Republic. She was whisked off to Holloway Jail

in London where she joined Maud Gonne and

Kathleen Clarke,

the other prominent women who challenged the

British government and their enforcers in

Ireland.

The

Irish Republic, Dail Eireann, and War of

Independence

In

November of 1918, after a general election was

called for December 14, the first election in

which women over thirty were allowed to vote and

run for office, Sinn Fein nominated Constance to

stand for the Dublin St. Patrick's Division

seat. While still incarcerated and unable to

campaign, she nonetheless outvoted the IPP

candidate by a margin of 7,835 to 3,741. Sinn

Fein garnered 73 of the 105 seats contested in

Ireland. On January 21, 1919, when the

first Dail Eireann (Irish Parliament) met in

the Mansion House in Dublin, Constance was one

of the 35 Teachtai Dail (deputies) who were

called out as 'Fe ghlas ag Gallaibh'

(imprisoned by the foreign enemy).

As

the first Dail Eireann met on January 21, nine

members of the Third Tipperary Brigade of the

Irish Volunteers ambushed a convoy transporting

explosives near Soloheadbeg in Co. Tipperary. In

the ensuing gunfight two members of the Royal

Irish Constabulary (RIC), were killed. That

ambush is widely regarded as the beginning of

the War of Independence.

On March

10, 1919, Constance was released from prison

with the rest of the Sinn Fein detainees. Maud

Gonne and Kathleen Clarke had been released a

few months earlier due to their deteriorating

health.

Constance

was appointed Secretary for Labor at the second

Dail Eireann meeting which was held on April 1,

1919. On June 15, 1919, she was arrested and

sentenced to four months' imprisonment for a

speech she had made in Newmarket in Co. Cork.

She served the sentence in Cork jail. While she

was still in prison, Dail Eireann, Sinn Fein,

Cumann na mBan, the Irish Volunteers, and the

Gaelic League were declared illegal. After her

release on October 18, 1919, she continued her

work as Secretary of Labor in the government of

the Irish Republic, arbitrating labor disputes

and attending meetings at various secret

locations.

In

November of 1919, an order was issued for her

arrest. For the following 10 months she was on

the run, moving around Dublin on her bike and

avoiding capture. On September 26, 1920, she

was arrested again on her way back to Dublin

after visiting Maud Gonne in Wicklow. She was in

a car driven by Sean McBride, Maud Gonne’s son.

On December 2, 1920, she was court-martialed

and sentenced to two years of hard labor in

Mountjoy jail for organizing the Fianna ten

years earlier. On July 24, 1921 Constance was

released after the Lloyd George/de Valera truce

went into effect.

Anglo-Irish Treaty, United States Lecture Tour

and the Treaty War

On October

2, 1921, a delegation headed by Arthur Griffith

was sent to London by de Valera to 'negotiate

and conclude on behalf of Ireland a treaty or

treaties of settlement, association and

accommodation, between Ireland and the British

Commonwealth'. On December 6, 1921, the

delegation relented to British pressure and

signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty (Treaty) that

violated the Proclamation of 1916, eviscerated

the Irish Republic declared in 1919, and set the

stage for a bitter war. Needless to say,

Constance opposed the Treaty as did the women of

Cumann na mBan by a vote of 419 to 63.

In April

of 1922 Constance traveled to the United States

accompanied by Kathleen Barry, sister of Kevin

Barry. The visit was arranged by de Valera under

the auspices of the American Association for the

Recognition of the Irish Republic. Because of

her drawing power and reputation as a die-hard

Republican, Constance

was added to a delegation already in the United

States that included Austin Stack, J.J.

O’Kelly, Father

Michael O'Flanagan,

and Brian O'Higgins. The delegation's tour, which included

every major city from coast to coast, was

greeted at every stop with fanfare, dignitaries,

and large crowds. The tour generated widespread

publicity regarding the undemocratic provisions

of the Anglo-Irish Treaty that eviscerated the

burgeoning Irish Republic and partitioned

Ireland into two entities subject to British

sovereignty. Due to support for the Treaty by

John Devoy

and Judge Cohalan of Clan na

Gael, the crowds that greeted the delegation in

New York were smaller than elsewhere in the

country. Nonetheless, Constance returned to

Ireland at the end of May 1922 having raised

$20,000, a sum equal to $275,000 in today's

currency.

On June

28, 1922, a month or so after Constance's return

from the United States, the Treaty War, aka the

Civil War, started with the bombardment of the

Four Courts occupied by anti-Treaty Republican

forces. From the onset, the anti-Treaty

Republicans were outnumbered, outgunned, and

underfinanced compared to the British-backed

Free State forces, aka the

National Army, who had unlimited

British-supplied armament, manpower, and funds

at its disposal. At the end of the war in May of

1923, the National Army of 58,000 was comprised

mostly of disgruntled 'Redmondites', Irish-born

Volunteers who joined the British Army to defend

its Empire during WWI. Having survived the

Western Front and Gallipoli, they returned to

Ireland, not as the heroes they expected to be,

but rather as misguided defenders of the British

Empire. In addition to the rank-and-file

Redmondites, the command of the National

Army was mostly in the hands of retired

high-ranking British Army officers. In essence,

the National Army was a British enterprise, a

bulwark to ensure the Free State would prevail

at any cost. Without the National Army it's

doubtful that the Free State would have survived

a civil war against the anti-Treaty Republican

side who garnered the support of two-thirds of

the Irish Republican Army's Volunteers after

terms of the Treaty were debated and signed.

Constance,

who was 54 at the time, did not stand idly by.

During the Battle of Dublin (June 28 to July 5)

she helped man a sniper position on the roof of

the Hammam Hotel on Henry Street. On July 5,

she was amongst the women ordered to leave the

burning hotel through the back door by

Commandant Cathal Brugha as he stormed out the

front door with blazing guns to provide cover.

He was mowed down and died two days later. After

July 5, the war moved to the countryside,

primarily to Munster where most of the ensuing

action took place. In the meantime, Constance

was on the run. While on the move she wrote

articles for pro-Republican publications in the

United States, helped the Women's Prisoners

Defense Fund, and delivered speeches in

Republican-held towns. On a number of occasions

she narrowly avoided capture. However, on

November 20, Constance's luck ran out when she

was arrested in Dublin while canvassing with

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington. She was first held in

the Bridewell Prison without charge before been

transferred to the North Dublin Union, a former

workhouse and British military barracks.

Immediately after her arrest she joined the

other Republican prisoners in an ongoing hunger

strike. Three days later, on November 23, the

hunger strike ended in all prisons. After

spending five weeks in prison, she was released

on Christmas Eve.

In the

1923 general election Constance won the Dublin

South constituency seat she vacated in 1922 in

opposition to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Like the

other successful candidates, she did not take

her Dáil seat in keeping with the Republicans'

abstentionist policy.

Fianna Fail and Death

After the

Treaty War ended, Constance remained active

within Cumann na mBan and Sinn Fein. She also

spent a considerable amount of time working with

the Fianna, especially after its reorganization

in 1925 when more emphasis was placed on

traditional Irish games, music and art,

scouting, and first aid. In 1925 she served on

the Rathmines and Rathgar District Council. She

also reengaged with the theater by helping to

establish the Republican Players Dramatic

Society and writing a number of plays that the

Society produced.

In March

of 1926, Sinn Fein held a meeting at the Rotunda

in Dublin to discuss the future of the party. A

number of their members, including Constance,

were concerned that the Free State party was

passing repressive and self-serving laws with

impunity, therefore they should take their Dail

seats contingent on the abolition of the Oath of

Allegiance to the British monarch specified in

the Treaty. After a motion to that effect was

defeated by the delegates, de Valera resigned as

the Sinn Fein leader and set up a new party,

Fianna Fail. Most of the Sinn Fein delegates

joined the Fianna Fail, including Constance.

In the

general election held in June of 1927 Constance

stood successfully as a Fianna Fail candidate in

the Dublin South constituency.

A month

later she fell seriously ill and was admitted to

Sir Patrick Dun’s hospital. She was suffering

from peritonitis that did not respond to the

available treatment at that time. Constance

Markievicz died at 1:25 a.m. on the morning of

July 15, 1927. Her husband, Casimir, who had

returned to his homeland in 1913 was by her side

as was

Dr. Kathleen Lynn. She is buried in Glasnevin

Cemetery, Dublin. It was estimated that

250,000 to 300,000 people

lined the streets of Dublin for her funeral.

She is

commemorated by a limestone bust in St.

Stephen’s Green, a plaque in St. Ultan’s

Hospital, a football ground, and in W. B.

Yeats’s poem, ‘In

memory of Eva Gore-Booth and Con Markievicz’.

Contributed by Tomás Ó Coısdealbha

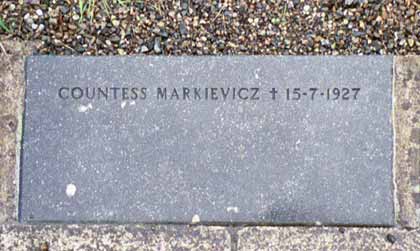

cemetery AND grave location

Name:

Glasnevin

Cemetery

ADDRESS: Finglas

Road, Glasnevin, Dublin 11, Ireland

LOCATION:

Republican Plot

REPUBLICAN PLOT

GRAVE MARKER

|