|

Margaret Skinnider (1892 -

1971)

Teacher, Suffragette, 1916 Easter Rising

participant, Paymaster General of the Republican forces.

Prisoner of the Free State, President of the Irish

National School Teachers’ Association 1956/7.

Margaret

Skinnider, the youngest of five children, was born to

James Skinnider and Jane Dowd on May 28, 1892 in Coatbridge on

the outskirts of Glasgow in Scotland.

Her father was born in Cornagilta in Co.

Monaghan and her mother in Barrhead in East Renfrewshire,

Scotland. Margaret

Skinnider, the youngest of five children, was born to

James Skinnider and Jane Dowd on May 28, 1892 in Coatbridge on

the outskirts of Glasgow in Scotland.

Her father was born in Cornagilta in Co.

Monaghan and her mother in Barrhead in East Renfrewshire,

Scotland.

In the latter half on 19th century Coatbridge was a booming town owing

to the discovery of large deposits of coal and iron ore and,

consequently, a choice locations for many of the Irish fleeing the “Great

Hunger” of 1845 through 1850. By 1851 the Irish constituted 35% of

the of the town’s population. By the turn of the 20th century that had

dropped to 15% owing to the depletion of the coal and iron ore deposits

and the consequent reduction in the work force needed to man the mines

and smelters.

Coatbridge was, and sometimes still is referred to as “little Ireland”,

a not so unique distinction in that it was applied to other towns and

areas in Scotland including the Cowgate in Edinburgh, the birthplace of

James Connolly. During Skinnider’s childhood it had an abundance of

Irish social, cultural and political organizations frequented and

supported by exiled Irish immigrants. The influence exerted by these

organizations on the attitudes and loyalties of the children growing up

in places like Coatbridge, particularly, with respect to Ireland and its

people, was the real deal as opposed to what they were taught in school

which, to them, was unbelievable and, generally, dismissed as

propaganda.

During her childhood she spent many of her summer vacations in

Monaghan with her father’s family. It was during these visits that she

witnessed, first-hand, the disparity in living conditions between the “Planter

class"(1) and the native Irish. That insight lent

credence to what she later read in a book titled “An Irish History of Ireland”. Comparing what she read

in that book to the British version taught in school, compounded the

resentment she first felt in Monaghan towards the British establishment

and, overtime, formed the basis for her lifelong militant political

activism.

After completing her primary and secondary education Margaret enrolled

in a teachers training college. On receiving her certification she

started her teaching carrier as a mathematics teacher at St Agnes’s

Catholic School in Lambhill on the north side of Glasgow.

By the time Margaret turned twenty she was deeply involved with the

militant suffragette movement in Glasgow. She was on the authorities

watch list of militant women who were quite capable and unafraid to

engage in militant activities in furtherance of their cause.

At the onset of WWI the British government set up rifle practice clubs for young

women who, if needed, would have the skills to help defend the British

Empire. Margaret joined one of the clubs, and unlike many of the other

young women who joined, pressed on with her training until she became an

excellent markswoman. Also, unlike many of the other young women, her

motivation was not to defend the Empire but, rather, to help break its

hold on Ireland, the country she considered to be hers.

Radicalized by her experiences as a militant suffragette, coupled with

empathy for the oppressed and

exploited working class and Ireland’s quest for freedom,

Margaret joined Cumann na mBan and the Irish Volunteers in the summer of

1915 after branches of both organizations were established in Glasgow.

She believed her suffragette related experiences and newly acquired

shooting skills would be useful assets in furthering the aims of both

organizations.

By 1915 Ireland was at a crossroads of history. Dormant revolutionary

forces, buoyed by the nationalistic fervor generated by the Gaelic

League and other nationalistic and labor organizations, were once again

preparing for war. A series of triggering events including the British

Empire at war, the abandonment of the third Home

Rule bill for Ireland and the high-jacking of the Irish Volunteers by

John Redmond set the stage for the ensuing Easter Rising of 1916.

Students of Irish history such as Margaret knew that the ‘Empire at

war’ was a trigger for an Irish rising.

Margaret zeal and hard work for Cumann na mBan in Glasgow came to the

attention of Countess Markievicz (2) who invited her to visit Dublin

during the Christmas season of 1915.

During the months leading up to the Easter Rising members of the Glasgow

branches of Cumann na mBan and the Irish Volunteers who travelled to

Ireland carried, hidden on their person, weapons on various description

including guns, ammunition and bomb detonators. Margaret, who smuggled a

quantity of bomb detonators with attached wires wrapped around her body,

was no exception.

It is worth noting here that as many as 50 active participants in the

Easter Rising came from Scotland including James Connolly who was

executed for his leadership role and Charles Carrigan from Denny in

Stirlingshire who was killed during the evacuation of the General Post

Office.

Countess Markievicz and Margaret were kindred spirits. Both were

courageous, excellent markswomen and fiercely dedicated to women’s

rights, the welfare of the downtrodden and Ireland’s inalienable right

to nationhood. From that perspective they understood and trusted each

other and in no time were planning, practicing and preparing for the

rising they were confident was inevitable.

To that end Margaret made use of her short visit to Dublin. Under Markievicz’s tutelage

she tried out various disguises that would be

useful during the rising including walking through the streets of Dublin

with the

Fianna

Eireann boys dressed as one of them -- singing anti-recruitment

songs to discourage young Irishmen from joining the British army. With

her mathematical background she was tasked by Markievicz to produce

detailed sketches of the Beggar’s Bush barracks for use in dynamiting

the barracks if the need arose during the rising. The sketches she

produced that included the placement of explosives, were reviewed and

approved by James Connolly who was familiar with layout of the barracks.

She also took part in raids for arms and ammunition and practiced

setting off explosives in the foothills of the Dublin mountains. By the

time her visit to Dublin ended she had gained the trust and confidence

of Markievicz and Connolly and others in leadership positions. She

promised Markievicz that she would return to Dublin when sent for,

probably before Easter 1916.

When summonsed, Margaret returned to Dublin, as promised, on Holy

Thursday. On arriving there she went to Liberty Hall, the headquarters

of the Citizens Army, where she joined other young women in assembling

and transporting munitions to hiding places and carrying dispatches to

outlying commanders. The orders issued by the Army Council to the Irish

Volunteers to assemble for drill on Easter Sunday morning was

countermanded by Eoin McNeill, Commander-in-chief of the Irish

Volunteers when he learned that the order to assemble was the signal for

the start of the rising.

O’Neill’s countermanding order, born of fear, coupled with the loss of

the

"Aud" and its cargo of munitions essentially doomed the rising to

failure.

With no options left due to the advanced stages of implementation and

the real possibility that the British would be alerted the Army Council

decided to reschedule the rising for Monday. They sent couriers around

the country to inform the Volunteer commanders that the rising was

proceed as planned a day later on Monday the 24th. Despite their best

efforts most of the Volunteer battalions, who were used to O’Neill’s

signature on orders, were hesitant to reverse course, fearing a British

plot.

At the onset of the rising on Monday morning, Margaret was sent out on

her bicycle to scout the barracks around Dublin to see if the British

army was on the move. On reporting back that all was quite she was sent

out again by Michael Mallin to Stephens Green with instructions to

return if she observed any unusual movement by the police or military

personnel, otherwise remain there until she was joined by the contingent

assigned to Stephens Green.

From Sunday through Wednesday Margaret carried numerous dispatches on

her bicycle between the Stephen’s Green garrison and headquarters in the

General Post Office. On many of these trips she came under fire. On one

occasion her bicycle tire was punctured by a bullet. On another occasion

she rode up behind a carriage occupied by Markievicz and another

volunteer who had come face-to-face with a contingent of British

soldiers. Markievicz and her companion, without hesitation, raised their

weapons and shot two of the soldiers leading the contingent. The rest

of the soldiers retreated.

By Wednesday British troops were pouring into Ireland. The College

Green garrison of 100 or so men and women, who were about to be

surrounded took over the nearby College of Surgeons building were they

remained until the surrender on Saturday the 29th. Between running

dispatches Margaret donned a Citizen Army uniform and joined the squad

nestled in the rafters firing at soldiers manning a machinegun across

the green on the roof of the Shelbourne hotel. According to her own

account she saw more than one soldier she had aimed fall.

On Wednesday Margaret presented Mallin with a plan, based on her

observation from the many dispatch runs she had undertaken, to dislodge

the British soldiers from the roof of the Shelbourne Hotel. At first

Mallin was reluctant to put her in charge of such a dangerous mission,

but, after Margaret argued that the Proclamation put men and women on

even footing reluctantly agreed. However, before allowing her to

undertaking that task he put her in charge of a group of men dispatched

to silence another machine gun nest setup on the nearby University

Church. The plan was to set fire to adjacent structures to dislodge the

nest.

In reaching the structure one of the men used his rifle butt to

breakdown a door to gain access. Unfortunately the rifle discharged

alerting nearby soldiers who opened fire, killing 17 years old, Fred

Ryan and wounding Margaret with three bullets in her back. She was

carried back to the College of Surgeons where she remained until the

Sunday morning. Shortly after arriving back at the College, Markievicz,

who had disappeared for a short time, informed Margaret on her return

that Fred’s killing and her wounding had been avenged. The two British

soldiers who had killed Fred Ryan and wounded Margaret lay dead on a

Dublin street.

After the surrender, Margaret was transferred to St. Vincent’s hospital

where she recuperated for five weeks after which she was taken to

Brideswell prison for questioning. After several hours of questioning

she was taken back to St. Vincent’s at the behest of the head doctor at

St. Vincent’s who had contacted the prison authorities insisting that

she was too ill to be jailed.

Shortly after been released from the hospital she, somehow, managed to

obtain a permit from the military authorities to visit Glasgow without

raising suspicion of her combatant role in the rising. During her stay

in Glasgow she went to England to visit prisoners-of-war who were

interned to English prisons after the rising.

In early August of 1916 Margaret, together with

Nora Connolly, left

Glasgow for the United States. After arriving there they embarked on a

fundraising lecture tour on behalf of the Irish National Aid Association

and Volunteer Dependants' Fund (INAAVDF).

In December of 1916

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington arrived in the United

States and took up residence with Margaret in Brooklyn. Hanna joined

Margaret and Nora on the fundraising lecture tour garnering substantial

sums of money for the INAAVDF and raising awareness of the dire

situation in Ireland in the aftermath of the rising.

In 1917 Margaret published a book while living in New York 'Doing my bit

for Ireland' that chronicled her involvement in the activities leading

up to and during the rising.

Towards the end of 1917 when the INAAVDF ceased its fundraising

activities Margaret, Nora Connolly and Hanna Sheehy Skeffington sought

permission to return to Ireland. At first their request was opposed by

the British Military authorities in Ireland fearing that they would

engage in activities detrimental to British interests in Ireland. After

numerous protests and adverse publicity, the British relented, and by

July of 1918 allowed the women to return to Liverpool, but not to

Ireland.

In short order all three of the women made their way back to Ireland.

Leading up to and during the War of Independence, Margaret, trained

Volunteers recruits in the use of firearms and explosives. She opposed

the so-called Anglo-Irish Treaty that brought an end to the war, as did

the vast majority of the women of Cumann na mBan.

Core provisions of that treaty included 1) the partition of Ireland, 2)

Irish people would continue to be subjects of the British Empire (not

Irish citizens) and 3) anyone seeking employment with the government or

any of its agencies as well as members of the Dail would be required to

swear an oath of allegiance to the English monarch.

Amongst other nefarious provisions of the treaty, the above three

provisions were the most repugnant to a majority of the fighting men and

women who, in good conscience could not abide by. The treaty was a

recipe for war.

At the onset of the ensuing Treaty War, Margaret was appointed Paymaster

General of the Republican forces. In December of 1922 she was arrested

by the pro-treaty British-backed Free State forces and incarcerated for

11 months in the North Dublin Union and Mountjoy jail under unsanitary

and atrocious conditions.

After she was released in late 1923 she went to work as a primary

teacher at the Sisters of Charity school in King’s Inn Street, Dublin

where she remained until she retired in 1961. She was also a prominent

member of the Irish National School Teachers’ Association serving as its

president in 1956/7. She also served on the Irish Congress of

Trade Unions executive council until 1963.

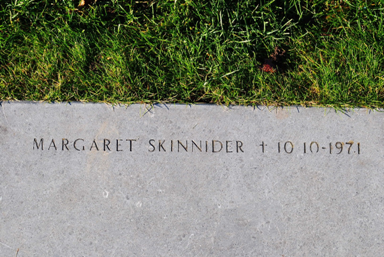

Margaret Skinnider died in October of 1971. She is buried in the

Republican plot in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin alongside Countess

Markievicz.

Contributor:

Tomás Ó Coısdealbha

NOTES:

1, The "Planter class" the term used by the native Irish

in referring to the Protestant Ascendancy — known simply as

the Ascendancy — was the political, economic and social domination

of Ireland by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy and members of

the professions, all members of the Established Church (the Church of

Ireland and Church of England) between the 17th century and the early

20th century. The Ascendancy excluded other groups from politics and

high society – widely seen as primarily Roman Catholics, but also

members of the Presbyterian and other Protestant denominations, along

with non-Christians such as Jews. Until the Reform Acts (1832–1928) even

the majority of Irish Protestants were effectively excluded from the

Ascendancy, being too poor to vote. In general, the privileges of the

Ascendancy were resented by Irish Catholics, who made up the majority of

the population (from Wikipedia)

2, Countess Markievicz, born Constance Gore-Booth, was a

product of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy. She was a suffragette, a

socialist and a fervent Irish nationalist. She was a founding member of

Fianna Eireann, a member of Cumann na mBan and an officer in James

Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army. She was second in command to Michael

Mallin at the Stephens Green/College of Surgeons garrison during the

Rising. She was sentenced to death for her role in the Rising that

commuted to life imprisonment because of her gender.

cemetery AND grave location

Name:

Glasnevin

Cemetery

ADDRESS: Finglas

Road, Glasnevin, Dublin 11, Ireland

LOCATION:

Republican Plot

REPUBLICAN PLOT

GRAVE MARKER

|