Elizabeth `Lily’

Kempson (1897 - 1996)

Irish Patriot, Labor

Activist, Citizen Army Volunteer, Veteran of the 1916 Easter Rising.

Elizabeth

Ann `Lily’ Kempson was born in Co. Wicklow, Ireland on Jan. 17, 1897.

She was the fifth of nine children born to James Kempson and Esther

Kempson (Moore). Her mother, Esther, who was born in Co. Wicklow, died

in 1919 during the flu epidemic. Her father, James, who was born in Co.

Carlow, died in 1940.

Elizabeth

Ann `Lily’ Kempson was born in Co. Wicklow, Ireland on Jan. 17, 1897.

She was the fifth of nine children born to James Kempson and Esther

Kempson (Moore). Her mother, Esther, who was born in Co. Wicklow, died

in 1919 during the flu epidemic. Her father, James, who was born in Co.

Carlow, died in 1940.

The family moved from Carlow to Dublin when Lily was still a young

child. They lived in abject poverty in a rundown 2-room tenement flat

in Piles Buildings off Golden Lane

with their maternal grandmother. Golden Lane is located on the south

side of the river Liffey close to the City Center. At

that time, housing conditions in Dublin for the working class were the worst of any city in

the United Kingdom.

Educational opportunities available to

Irish children, including Lily

and her siblings, were tenuous at best. Although compulsory education for

children, age 6 to 14, was mandated by the Ireland Educational Acct of

1892, several provisions contained therein, including one that required

only 73 days of compulsory attendance, rendered the benefits of the Act

marginal at best. In addition to that damaging provision, the Catholic

Hierarchy objected on the basis that the Act subverted parental

authority over children's education, a right, they claimed, existed in

natural law. That claim had more to do with maintaining control over

their flock; a task made easier with a less educated populace.

Despite such obstacles, Lily managed to

attain a good basic education; reaching a level consistent with a keen

intellect and a good school attendance record. Not all of Lily’s piers

raised in the Dublin slums, grasped the true nature of their situation

nor the social inequities that imposed on them an unjust and inhuman

burden. Centuries of subjection had left them with a defeatist

attitude, to the extent that they

accepted vassalism as a fact of life, a burden to bear, a legacy

not to be challenged. Although born into the same social environment,

Lily did not subscribe to that defeatist attitude; her involvement in the

Dublin lockout of 1913 and in the 1916 Easter Rising bears testimony to

that fact.

Lily entered the work force at the age of

fourteen, finding work at the nearby Jacob's Biscuit Factory on Peters

Row. At that time, working conditions in Dublin, as elsewhere in the

industrial world, were atrocious. A sixty to eighty-hour work week, for

low pay, under dangerous and unhealthy conditions, was the norm. It was

worse still for women and children who were paid a fraction of what men

were paid for the same line of work.

During a rally to unionize women

workers in Dublin in the spring of 1911, Delia Larkin, James Larkin’s

sister, condemned Jacob’s corrupt management for the debasement of their

women employees. After describing the degrading methods used by Jacob’s

to humiliate and threaten the women and young girls working there, she

concluded her speech by stating that:,

‘Jacobs & Co. have no qualms of conscience whatever as far as the

workers are concerned; they are out to make a profit, and make it they

will, even though it be at the cost of ill-health and disablement to the

girls, women, and men of Dublin

On August 22, of that year, 470 bakers at

Jacobs, led

James Larkin, went on strike for better pay and working

conditions. One day later, 3,000 women workers, including fourteen-year

old Lily Kempson and eighteen years old Rosie Hackett walked off the job

in support of the bakers. Due in part to women’s show of solidarity, the

strike was settled with the workers gaining better wages and working

conditions.

After that shared experience, Lily and

Rosie Hackett became close friends and comrades. They became members of

Larkin’s Irish Transport and General Workers Union

(ITGWU) and participants in two of the

most historic events of the 20th century in Ireland; the 1913

industrial lockout and the 1916 Easter Rising

On Saturday August 30, 1913, a dispute arose in Jacob’s factory when a

lift operator refused to handle flour from Shackelton’s Mill where a

strike was in progress. Jacob’s fired the operator resulting in a

walkout by other members of the ITGWU. When some of the workers returned

to work the following Monday, they found a notice posted on the

factory door by the management stating that,

‘it was reluctantly

compelled to shut down for an unknown period of time’.

The reason for the ‘compelled’ shutdown was due to a ploy by

Jacob’s, and over 300 other businesses in Dublin to break the ITGWU, by

demanding their employees revoke their ITGWU membership and sign a

pledge of fealty to their employers as a condition of future employment. Their

leader and instigator was William Murphy, the owner of Clery's Department store.

The ensuing lockout was the most severe and significant industrial

dispute in Irish history. Early in 1914, after eight months, the

lockout ended in, at best, a draw. Union workers gained nothing and, by

the same token, a great number of businesses went bankrupt. The British

government, who stood behind the employers, was the ultimate winner when

thousands of laid-off workers joined its army only to be sent to the

Western Front and to the far-off Dardanelles to defend their very own

nemeses, the British Empire.

Lily did not stand idly by and wait for the lockout to end to get her

job back. As a member of the ITGWU she did picket duty and helped man

the soup kitchens at Liberty Hall, the Union’s headquarters. It

was while working there that she met many of Ireland’s revolutionary

women including

Maud

Gonne, Constance Markievicz,

Helena Molony,

Madeleine ffrench-Mullen,

Dr. Kathleen

Lynn, and many other fearless women who worked tirelessly day and

night to help the families of the striker’s. Most, if not all, of the

women she met there would go on to become participants in the Easter

Rising

In mid-November, during a stint on picket duty outside of Jacob’s,

Lily approached a young woman strikebreaker (a scab) to ask her not to

cross the picket line. A policeman who watched the exchange between Lily

and the strikebreaker accused Lily of accosting the strikebreaker and

placed her under arrest. It’s doubtful if 16-year old Lily,

laid hands on the woman, nonetheless, she spent a month in his majesty’s

Mountjoy jail, a victim of imperial justice --- a very young

“felon of

our land”.

Needless to say, Lily did not

return to her job after the lockout ended. Being a union member and an

activist, no business would hire her, especially when they found out

that she was a guest of British vassals in Mountjoy jail. With little prospect of finding work in Dublin, she journeyed

north to Belfast hoping to find work there.

James Connolly, whom she had

met in Liberty Hall during the lockout offered her room in his home

while searching for a job. During her unsuccessful job search in

Belfast, she became a member of the Irish Citizen Army, a workers

militia established by Larkin, Connolly and other ITGWU leaders in

November of 1913, at the height of the lockout. The purpose of the

workers militia was to protect demonstrating workers from attack by the

police and hooligan strike–breakers brought in from English slums.

After returning to Dublin, Lily

worked for the ITGWU out of Liberty Hall.

On the morning of the Easter Rising, April 24, 1916, Lily

left her home in the early hours of the morning and made her way to

Liberty Hall, one of the five mustering points selected by the Military

Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Four hundred men and women

of the Irish Citizen Army and the Irish Volunteers assembled there under

the overall command of James Connolly, Of these a detachment of about

100 men and women, under the command of Michael Mallin and Constance

Markievicz were dispatched to occupy St. Stephens Green. Lily was

assigned to that group. During Monday afternoon they dug trenches and

setup barricades at all entry points.

On Tuesday morning, Lily and her comrades came under fire from the

nearby Shelbourne Hotel from British troops who had occupied the hotel

overnight. At one point during the fighting, Lily prevented a volunteer

from deserting by holding him at gunpoint and reminding him that they

were in this together and no one was leaving. On Tuesday morning, Mallin dispatched small groups to occupy several buildings around the

Green, including the College of Surgeon, located diagonally across the

Green from the Shelbourne Hotel. Lily was assigned to that group.

Later on Tuesday when the situation on the Green became untenable, Mallin and the

remainder of his contingent fell back to the College of Surgeons, For

the remainder of the week, Lily attended to the injured, supported

defensive fighting positions and ran dispatches back and forth between

the College of Surgeons and the General Post Office (GPO).

The GPO was the Headquarters from where

Padraic Pearse,

James Connolly, Joseph Plunkett, Sean MacDermott,

Thomas J. Clarke received

dispatches from, and issued orders to the various garrisons.

When the order to surrender was issued by Pearse on

Saturday April. 28, Lily had left the College of Surgeons on a dispatch

run to the GPO. Although she avoided immediate arrest and

detention, her mane was on the list of wanted Citizen Army members

involved in the Rising According to her own accounting in later

years, she avoided the ensuing roundup of

suspects by hiding in

the Carmelite Church

confessional that Saturday night

and on Sunday morning mingled with the people attending Mass.

At some

juncture in her escape saga, she managed to get possession of her

sister's passport and make her way to the United States via Liverpool.

Her destination in the United

States was Seattle in Washington State where an uncle lived.

Shortly after settling down there

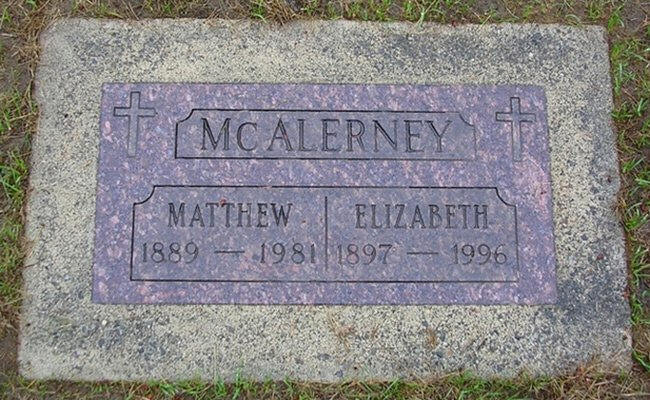

she met her future husband, Matthew McAlerney from Co. Down whom she

married in February of 1917.

This narrative is but a sketch of

Lily Kempson early years in Ireland. She was a fearless soldier for Ireland's

freedom and a champion for the working poor. She went on to live a full life in

the United States where, together with her husband Matthew, raised and

cared for a family of seven children, Though her work ethic and sense of

social responsibility she contributed enormously to

the American way

of life.

During her long and fruitful life,

she remained faithful to the Irish Republic, for which, she, as a young women,

put her life on the line.

Lily died on January 21, 1996 at

the age of ninety nine, the last surviving

Volunteer of the 1916 Easter Rising.

Contributed by

Tomás Ó Coısdealbha

CEMETERY

NAME:

Holyrood

Catholic Cemetery

ADDRESS:

205 Northeast 205th Street, Shoreline, WA 98155

GRAVE MARKER