John Daly,

the sixth of seven children, was born to John and Margaret Daly,

née Hayes in Limerick City, on October 18, 1845. His entry into

the world coincided with the onset of the Great Hunger, a

cataclysmic event in Irish history that spawned evictions, death

and inhumanity, in a land of plenty. It also resulted in the

banishment of over one million refugees to England, Scotland,

Wales, North America, and Australia. For many, the ships that

carried them to North America and Australia, became their

coffins, and the seas they crossed became their graves.

John Daly,

the sixth of seven children, was born to John and Margaret Daly,

née Hayes in Limerick City, on October 18, 1845. His entry into

the world coincided with the onset of the Great Hunger, a

cataclysmic event in Irish history that spawned evictions, death

and inhumanity, in a land of plenty. It also resulted in the

banishment of over one million refugees to England, Scotland,

Wales, North America, and Australia. For many, the ships that

carried them to North America and Australia, became their

coffins, and the seas they crossed became their graves.

It was during that ongoing tragedy that John lived his infancy

and early childhood years; too young to grasp what was happening

around him. He came of age in its aftermath, a period of

widespread emigration, stepped-up British army recruitment for

the Crimean War, the Catholic Churches recruitment for the Papal

Wars, and the ongoing institutionalized exploitation of tenant

farmers and agricultural workers by landlords and their agents.

Nothing had changed for the underclass who survived the Great

Hunger; life continued as before.

John received his primary education at the local national school

and, afterwards, at the Sexton St. Christian Brothers School.

As Irish history and the Irish language were not subjects

taught at school; after all, such subjects would be a hindrance

to the ongoing effort by the British government to anglicize the

Irish people. What John and his siblings learned of Irish

history was from his parents, whose families were staunch Irish

Republicans. John’s paternal grandfather was a member of the

Society of United Irishmen of 1798.

On reaching the age of sixteen John joined his father at the

James Harvey & Son's Timber Yard as lath splitter.

In 1863, at the age of eighteen John joined the Limerick Circle

of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). From the very

beginning he was dedicated to the aims of the organization and

worked tirelessly recruiting and training new members,

manufacturing and procuring weapons and ammunition for a future

rising.

The IRB was a secret oath-bound organization, founded on St.

Patrick’s Day in 1858 in Dublin by James Stephens,

Thomas Clarke

Luby, James Denieffe, Garrett O'Shaughnessy and Peter Langan,

most, if not all, were veterans of the abortive 1848 Rising. The

aim of the IRB was to make Ireland an independent Democratic

Republic by any means possible including by armed force. A

sister organization, named the Fenian Brotherhood, was founded

in New York around the same time by

John O’Mahony, Michael

Doheny and other exiled veterans of the 1848 Rising.

[The name “Fenian” was an umbrella term used to describe the

transatlantic partnership of the Fenian Brotherhood in America

and the Irish Republican Brotherhood in Ireland. A member of

either organization was generally referred to as a “Fenian”. It

will be used interchangeably in this narrative.]

Once committed to the cause of Ireland’s freedom, John never

wavered nor walked away from the challenges and danger that were

part and parcel of that commitment. From the onset, he was fully

involved despite the Catholic Church’s stance of denouncing

organizations and excommunicating their members who opposed

British rule in Ireland. As a victim of that dictum, John

decided to go around the Church and intercede directly with God.

After the failed United Irishmen Rising of 1798 and the

subsequent retaliatory enactment of the 1801 Act of Union by

England, most Irish nationalists believed that national

independence would never be achieved through constitutional

means. The Young Ireland Rising of 1848 and the aforementioned

rising of 1798, took place after constitutional means failed to

achieve a modicum of freedom for the usurped Irish people.

Based on that fact, the IRB concluded that British would never

grant Ireland independence and that physical force was the only

alternative available to them to achieve independence and free

the people from serfdom. They did so, knowing that physical force

used against the British Empire would be considered treason

under the Empire’s so-called rights and laws of conquest.

Despite that, the IRB was willing to use force to reclaim Irish

ownership of the land based on the principle of prior ownership

as well the rights of the Irish people to citizenship based on

their standing as people of an island nation with their own

language and other unique cultural traits.

The rising, originally scheduled to take place in 1865, was

foiled by the British after they came in possession of documents

lost by an emissary from the Fenian Brotherhood in America that

contained details for the planned Rising. They were also in

possession of collaborating information provided by the

informer, Pierce Nagle, who worked in the IRB’s newspaper

office. Acting on that information, the British raided the

newspaper office and arrested several of the IRB leaders

including John O’Leary, Thomas Clarke Luby and

Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

Shortly afterwards, Stephens and several other leaders were

arrested.

After the arrest and imprisonment of the IRB leadership, the

organization regrouped and continued to plan and prepare for a

Rising, with the help of the Fenian Brotherhood in America. In

support of that resolve, the Limerick City Circle set up a

workshop, near where the Daly’s lived, where they manufactured

ammunition and various handheld weapons. The location of the workshop

and the men who worked there was given to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)

by an informer, probably for a mere pittance or a pat on the

back; a commonplace happening in Irish history. Consequently, Daly and

his brother, Edward, and others were arrested on November 22,

1866, and imprisoned in Limerick Jail. On February 23, 1867,

they were released on bail, after having tortured their jailers

for three months with a continuous cacophony of Irish rebel songs.

On March 5, 1867, two weeks after Daly’s release from jail, the

Rising that was foiled in 1865 commenced with outbreaks in

Dublin, Drogheda, Cork and Limerick. From the onset, nothing

went right for the IRB volunteers and their Fenian comrades from

America who had crossed the Atlantic to fight in common cause.

Unbeknownst to the men in the field, General Massey, who was in

command of the uprising was betrayed by the traitor J. J.

Croydon, arrested and imprisoned. Without a central command the

uprising failed to spread as anticipated.

In Limerick City, Daly took charge of the IRB volunteers

mustered there. Aware that they could not successfully attack

the British forces stationed there, whose numbers and armament

dwarfed theirs, they headed south to join with other volunteers

to attack the Kilmallock RIC barracks and capture the weapons

housed there. That maneuver was consistent with the Rising’s

overall strategy i.e., attack RIC barracks and coastguard

stations, capture weapons and engage in a widespread guerilla

campaign. Lacking guns or explosives they were unable to breach

the fortified barracks and had to withdraw under heavy fire,

when RIC reinforcements arrived. Three volunteers were killed

and many more captured, seven of whom were transported to

Fremantle in Western Australia aboard the

Hougoumont

the last

convict ship to sail to Australia.

Daly evaded capture and went into hiding while planning his

escape out of Ireland. With the help of allies, he was smuggled

aboard a vessel departing Limerick for Liverpool. From there he

made his way to London where he booked passage to New York.

Daly spent the next two years in the United States. He worked at

several menial jobs until he met up with some of the American

Fenians who helped him find a job as a brakeman on the railroad

system.

In 1869, an amnesty campaign to free political prisoners, had

taken root in Ireland. The campaign was fronted by Isaac Butt,

an Irish member of the British Parliament as well as the

barrister who defended several of the Fenian leaders during the

so-called Fenian trials. By October of that year the campaign

was gaining momentum, attracting tens of thousands to meetings

throughout the country. The rhetorical skills of the speakers

in describing the role of packed juries, schooled witnesses and

biased judges at play during the Fenian trials was exposing the

British colonial judicial system in Ireland to international

condemnation. With few options to counter the campaign’s

momentum the British relented and started to release prisoners.

Daly believed that the amnesty campaign had severely damaged the

British government’s ability to continue arresting Fenians,

thus, clearing the way for his return to Ireland.

Once back in Ireland, he returned to his old job at the timber

yard. He also resumed his activities as an organizer and

agitator former for the IRB, particularly to affect the release

of Fenians still languishing in prisons in Ireland, England and

Australia.

In 1871 he was appointed the IRB’s organizer for Ulster. In

1872 he was elected representative for Ulster on the IRB Supreme

Council and shortly thereafter was appointed National Organizer.

It was in that position that he helped elect John Mitchel as a

Member of Parliament for Tipperary. He was also responsible of

enlisting

Thomas J. Clarke and other prominent figures in the

IRB ranks.

He was intolerant of anyone or any group with an agenda that did

not include the release of Fenian prisoners. In November of 1869

he, rightly or wrongly, prevented a demonstration by a tenants

rights group from taking place in the city because the release

of Fenians was not on their agenda. He was arrested and

acquitted in 1876 for disturbing a Home Rule meeting being held

to honor Isaac Butt, even though Butt was a prominent defender

of Fenian prisoners. His rationale was that Home Rule campaign

conflicted was the aims of the IRB.

Circa 1880, a group of dissident

members within Clan na Gael (the successor to the Fenian

Brotherhood) in the United States had opted to wage war against

British military and industrial target --- not in the Irish

countryside as before, but on the British mainland. Led by the

American based Fenian, Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa, the group took

part in a Dynamite Campaign that started in January of 1881 when

a bomb exploded at a military barracks in Salford, Lancashire

and ended four years later, in January of 1885 with a series of

bombs exploding in the House of Commons, in Westminster Hall and

in the Banqueting Room of the Tower of London

In August of 1882 Daly delivered the oration at the grave of

Charles J Kickham in Mullinahone, Co. Tipperary. Shortly

afterwards he went to the United States where he gave speeches,

spent time with, John Devoy, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and other

Fenian leaders. After a year, or so, in The United States he

departed for Birmingham in England where he met up with James

Egan, an old Fenian friend from Limerick.

By then, having been in the forefront of the Fenian movement for

a considerable length of time, Daly had earned himself a place

on Britain’s intelligence services watch list. He was under

surveillance from the moment he arrived in Birmingham. It’s

unknown if he was there to participate in the Dynamite Campaign

or not, but, having met with O’Rossa in the U. S. would suggest

that he had.

Irrespective of his intent, he was arrested on April 11, 1884 at

Birkenhead railway station in Liverpool, in possession of four

parcels of explosives. Following his arrest, James Egan’s home

in Birmingham was searched and, allegedly, nitroglycerine was

found buried in his backyard. Daly and Egan were tried at

Warwick Assizes on August 30, 1884, on treason felony charges,

found guilty and sentenced to penal servitude --- Daly for life

and Egan to 20 years.

He began his life sentence in Chatham prison in Kent. He was

later moved to Pentonville Prison in London and eventually to

Portland Prison in Dorset. During the twelve years he spent in

prison, he suffered cruel and inhumane treatment at the hands of

the prison authorities as did other Fenian prisoners. He was

released in 1896 after going on hunger strike. James Egan was

released in 1893.

While in prison he was nominated by the Irish Parliamentary

Party to contest the Limerick City seat in the 1885 General

election. He was elected but barred from taking his seat.

After his release from prison in August of 1896, Daly joined

Maud Gonne, the English-born Irish revolutionary, suffragette

and actress, who was campaigning in England for the release of

Fenian prisoners held in British prisons. The campaign was

arranged by the Irish National Amnesty Association. After

completing that tour,

he departed for the United States where he went on a lecture and

fundraising tour organized by John Devoy of behalf of Clan na

Gael. A percentage of the proceeds were given to Daly for his

efforts and to help him start a new life after his many

sacrifices and years of lost freedom for the Irish Republic that

Wolfe Tone gave his life for.

On his final return to Limerick city in 1898 he set up a bakery

on Williams Street with his share of the proceeds from his

lecture and fundraising tour in the United States. The signs

over his store front and his delivery vans were in Irish.

Being a realist and a feminist, he left the running of the

business to his deceased brother's daughter, Madge. Once

the business was up and running and in good hands he turned his

attention to politics.

As a working-mans politician, he served on the Limerick City Council from 1809 to 1906 and was

the Major of Limerick from 1899 to 1902. During his term as

Major he granted Thomas J. Clarke and Maud Gonne the Freedom of

Limerick,

the highest honor that Limerick City and County Council can

bestow on any individual.

He also

removed the Royal coat of arms from the Town Hall and added a

link to the mayoral chain depicting Irish revolutionary symbols.

John remained

forever faithful to the Fenian cause that he dedicated his life

too. Ever willing to help, he funded the Irish Freedom

newspaper founded by Thomas J. Clarke in 1910. He also funded a

drilling hall for Na Fianna Eireann on his property.

His home in

Limerick became a place of pilgrimage to the new generation of

Fenians including Thomas J. Clarke, his nephew Edward Daly, Sean

MacDiarmada, Ernest Blyth, Bulmer Hobson,

Padraic Pearse and

many other heroes of the 1916 Easter Rising. Confined to a

wheelchair, he lived through the anxious days of the Rising

worried about the young men and women manning the garrisons and

frustrated that he was could not take part.

John Daly, the Fenian, died

at his home in Limerick on

June 30, 1916.

Contributor:

Tomás Ó Coısdealbha

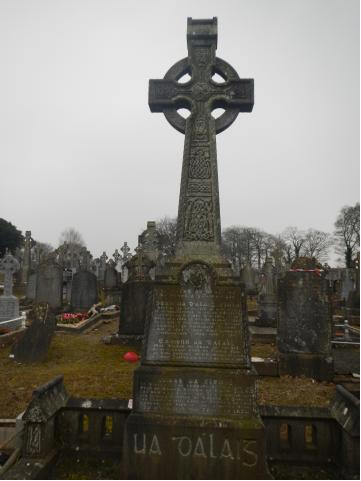

cemetery

NAME: Mount

St Lawrence Cemetery

ADDRESS:

The Gables, Limerick City, Co. Limerick,

Ireland

GRAVE

Click on above image to view

headstone inscription

|

Posted 02/08/2018 |